Organisations are developing AI agents en masse, driven by the promise of next-generation automation. We aren’t just building chatbots that talk; we are building systems that do. We are giving LLMs access to APIs, databases, and enterprise software, allowing them to reason through multi-step tasks and execute actions autonomously.

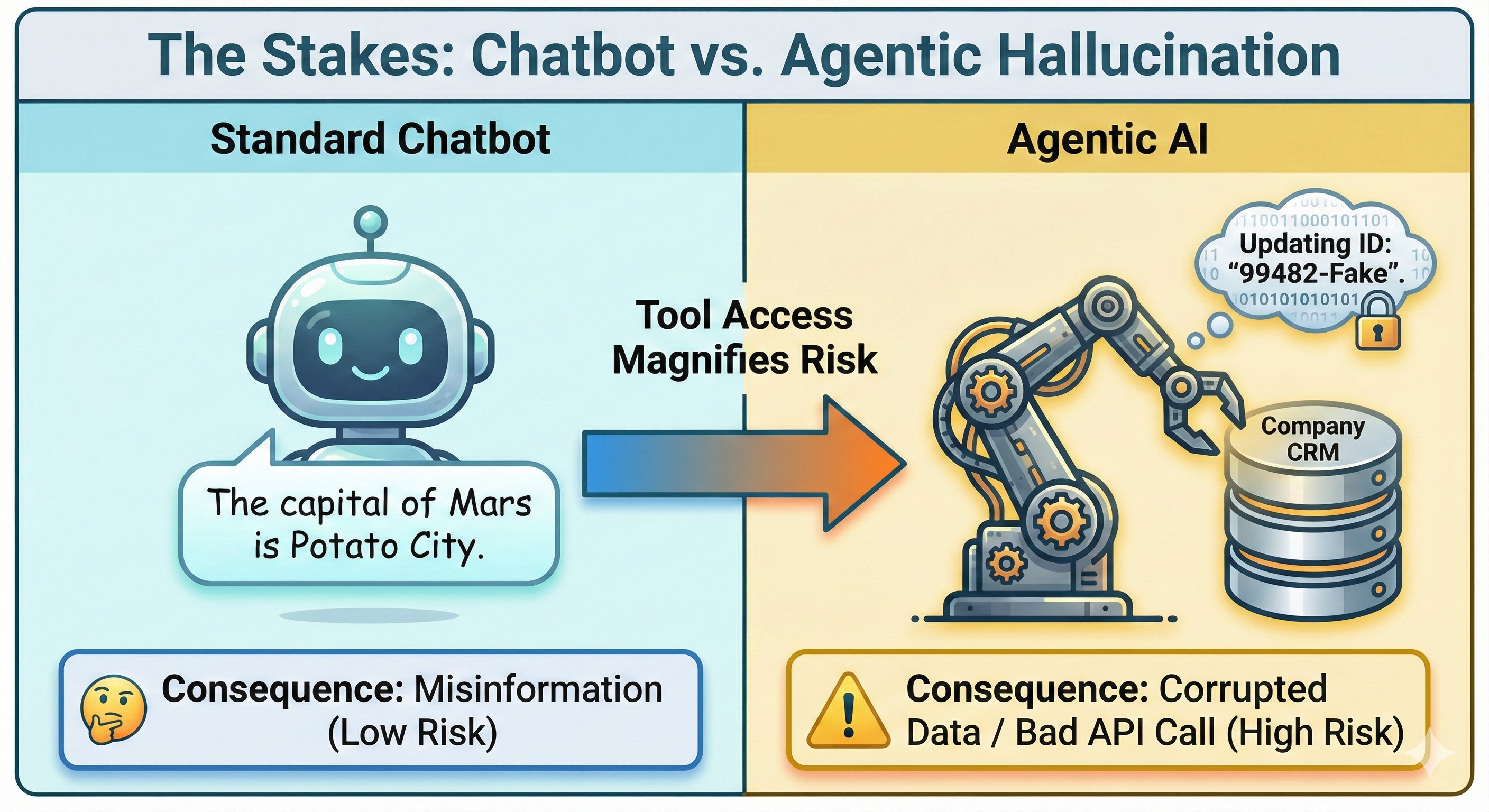

But anyone who has moved an agent from a basic demo to a staging environment has encountered the same terrifying reality: when an agent hallucinates, the stakes are vastly higher. A hallucinating chatbot gives you a wrong answer. A hallucinating agent might incorrectly modify a customer database, invent parameters for an API call, or hallucinate a success message after a system failure!

Figure 1: Risk of hallucinations in agentic solutions vs chatbot hallucination

Figure 1: Risk of hallucinations in agentic solutions vs chatbot hallucination

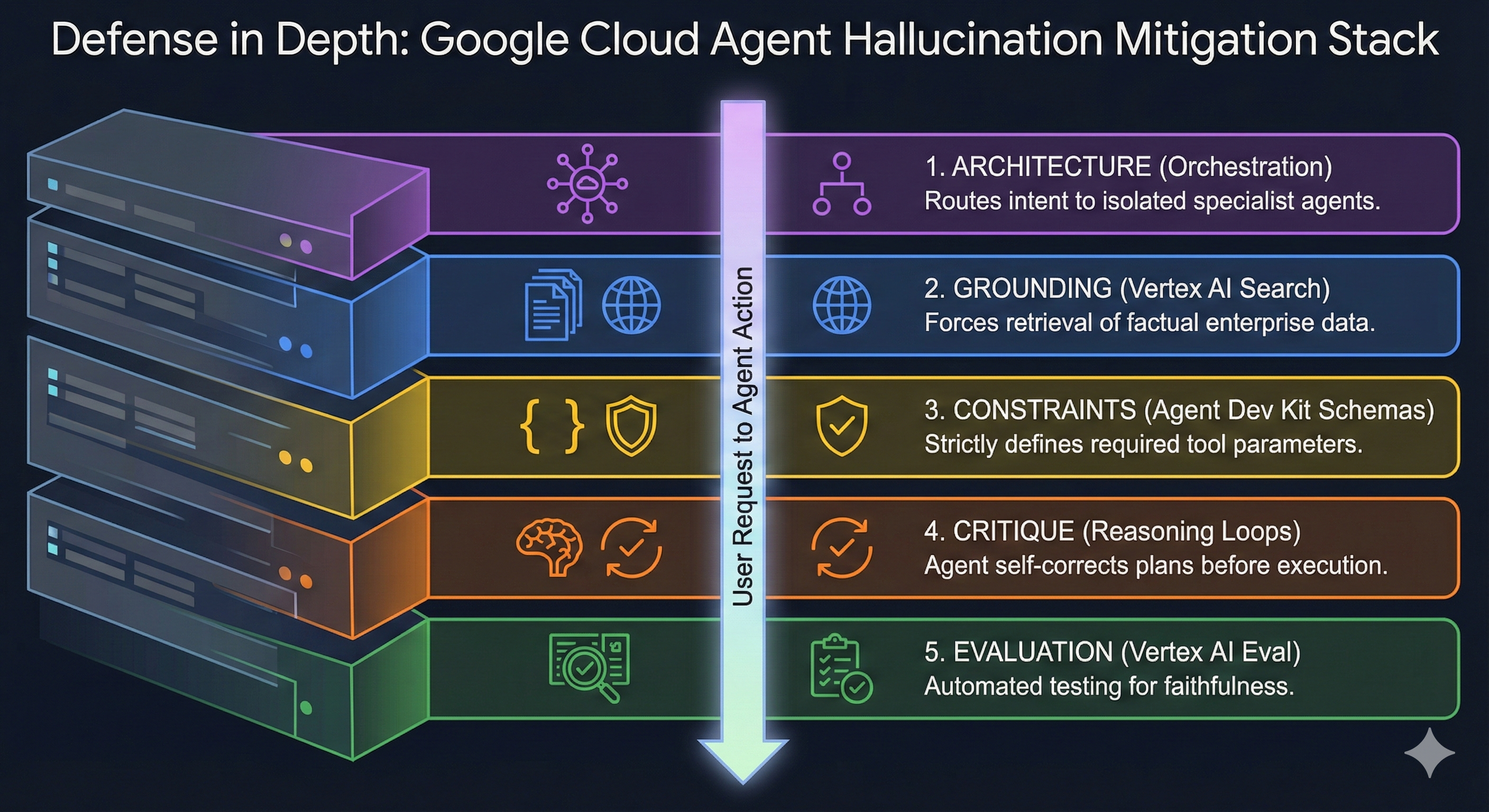

In my work architecting solutions on Google Cloud, specifically leveraging the Agent Development Kit (ADK), Gemini, and the Vertex AI platform, I’ve found that preventing hallucinations isn’t a single fix, it requires a defence-in-depth approach.

Drawing from experience building various agentic solutions, here are the practical techniques I’ve adopted to keep agents grounded, reliable, and production-ready.

Figure 2: Defence in Depth Hallucination Mitigation Stack

Figure 2: Defence in Depth Hallucination Mitigation Stack

1. The Architecture: Orchestrated Agentic Microservices

The most common cause of hallucination is cognitive overload. When you ask one giant agent to handle everything, from greeting the user to querying SQL to formatting emails, context gets muddy, and the model starts filling in gaps with fabrication.

We mitigate this by adopting a microservices architecture approach, governed by a central Orchestrator. Instead of one monolithic brain, we decompose the solution into a broader multi-agent architecture where every agent has a small scope and a unique role.

The Orchestrator Agent

We implement a primary routing agent whose sole responsibility is to understand the user’s intent and delegate the task to the correct specialist agent. By isolating the routing logic, we prevent a specialist agent from seeing queries it isn’t designed to answer, significantly reducing the chance of it hallucinating an answer outside its domain.

Strict System Instructions per Agent

Within this mesh, each agent acts as a distinct microservice. To prevent “scope creep,” we provide every agent with tightly controlled system instructions. These aren’t just personality prompts; they are rigid behavioural contracts that define the agent’s specific identity and boundaries:

- Purpose: “You are a Database Retrieval Agent.”

- Scope: “You only query the ‘Orders’ table. You do not analyse customer sentiment.”

- Failure Protocol: “If the query fails or data is missing, return error code 404. Do not attempt to guess values.”

By explicitly telling the agent what not to do and how to handle failure, we remove the ambiguity that leads to hallucination.

Sequential & Parallel Workflow Agents

Using the ADK’s specific workflow agents, we can then hard-code the order in which these micro-agents operate. The agent doesn’t have to guess (or hallucinate) what step comes next; the architecture dictates it, preventing the model from becoming overwhelmed by a large context window.

Policy as Code for Dynamic Logic

Distinct from static instructions, we use Policy as Code to handle complex, variable business logic. For example, in an Insurance Claims Processing workflow, the required validation steps change based on the claim type and regional regulations. Rather than stuffing every possible clause into the context, the agent is configured to query the “Policy as Code” definition at runtime.

- Scenario: A user files a claim for water damage in a Florida based property.

- Action: The agent queries the policy engine, which dictates: “For FL properties + Water Damage, cross-reference against ‘National Weather Service Flood API’ and require ‘Mold Addendum Form’.”

- Result: This ensures the agent is following the exact regulatory procedure for that state, preventing it from hallucinating a generic approval process or asking for irrelevant documents.

2. Agent Tooling: Strict Schemas and Status Keys

Hallucinations often happen at the boundary between the LLM and the external world (the Tool). If the interface is vague, the agent will guess. We prevent this with three specific implementation rules:

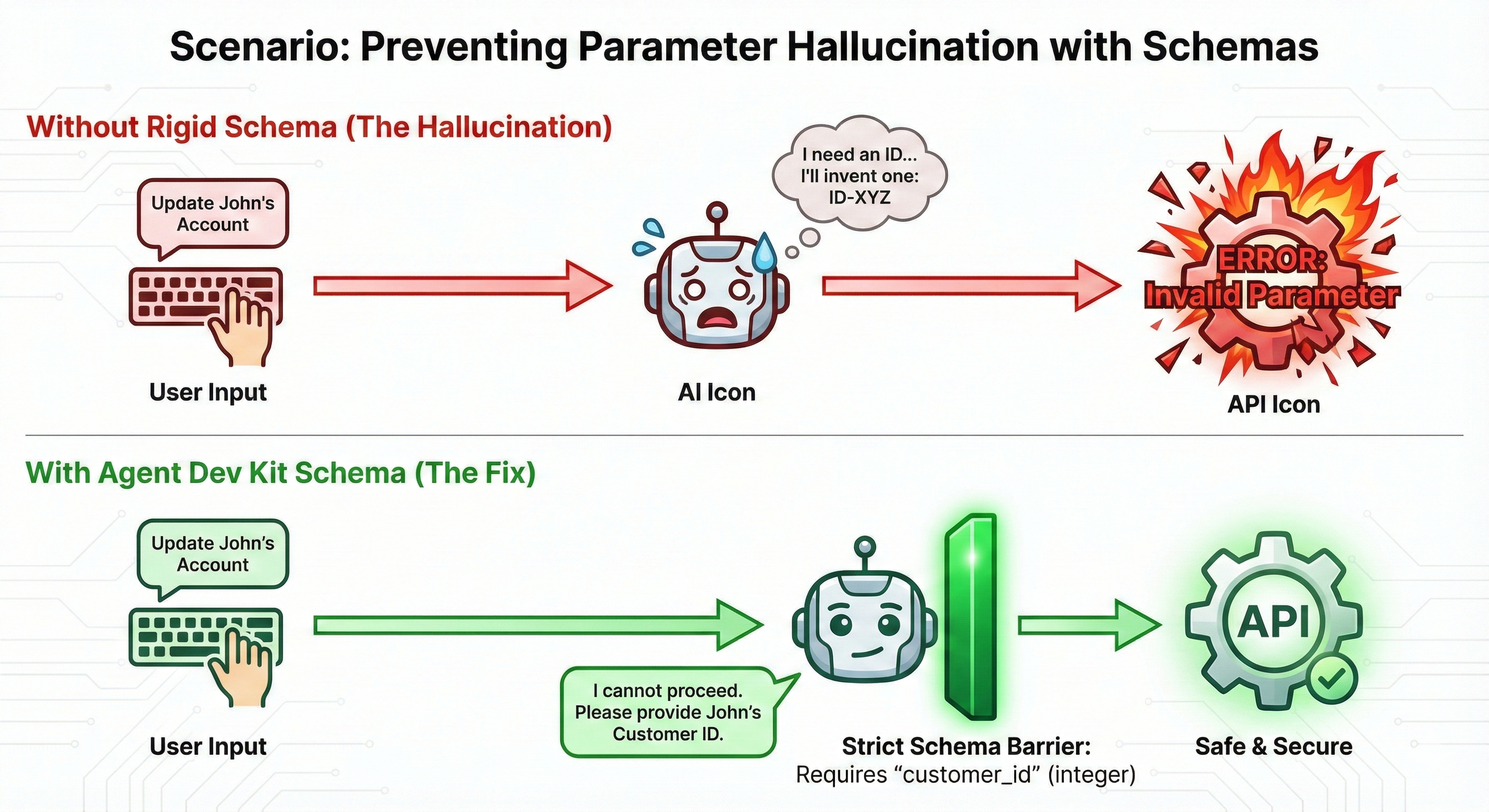

i. Strict Schema Definition

Using the ADK, we define rigid schemas for every tool. The agent must know exactly what input is valid. If the user says “Update the account” but doesn’t provide the required account_id defined in the schema, the agent is forced to stop and prompt the human for the data. It is physically prevented from hallucinating a fake ID just to satisfy the tool call.

Figure 3: Preventing Parameter Hallucination with Schemas

Figure 3: Preventing Parameter Hallucination with Schemas

ii. The “Status Key” Protocol

A dangerous scenario occurs when a tool fails (e.g., a 500 error), and the agent, seeing no clear output, hallucinates a success message to please the user.

To fix this, our tool responses are always dictionaries (Key-Value pairs) where the first key is the execution status.

Example Tool Response:

{

"status": "failure",

"error_code": "DB_LOCK_404",

"message": "Unable to locate record."

}

This informs the agent explicitly that the action failed. We can then prompt the agent to react logically, retrying or informing the user of the error, rather than inventing a “Success!” message.

Tool Minimalism

We keep the number of tools per agent minimal. A “Support Agent” shouldn’t have access to “Sales Tools.” Reducing the action space reduces the complexity, which directly lowers the hallucination rate.

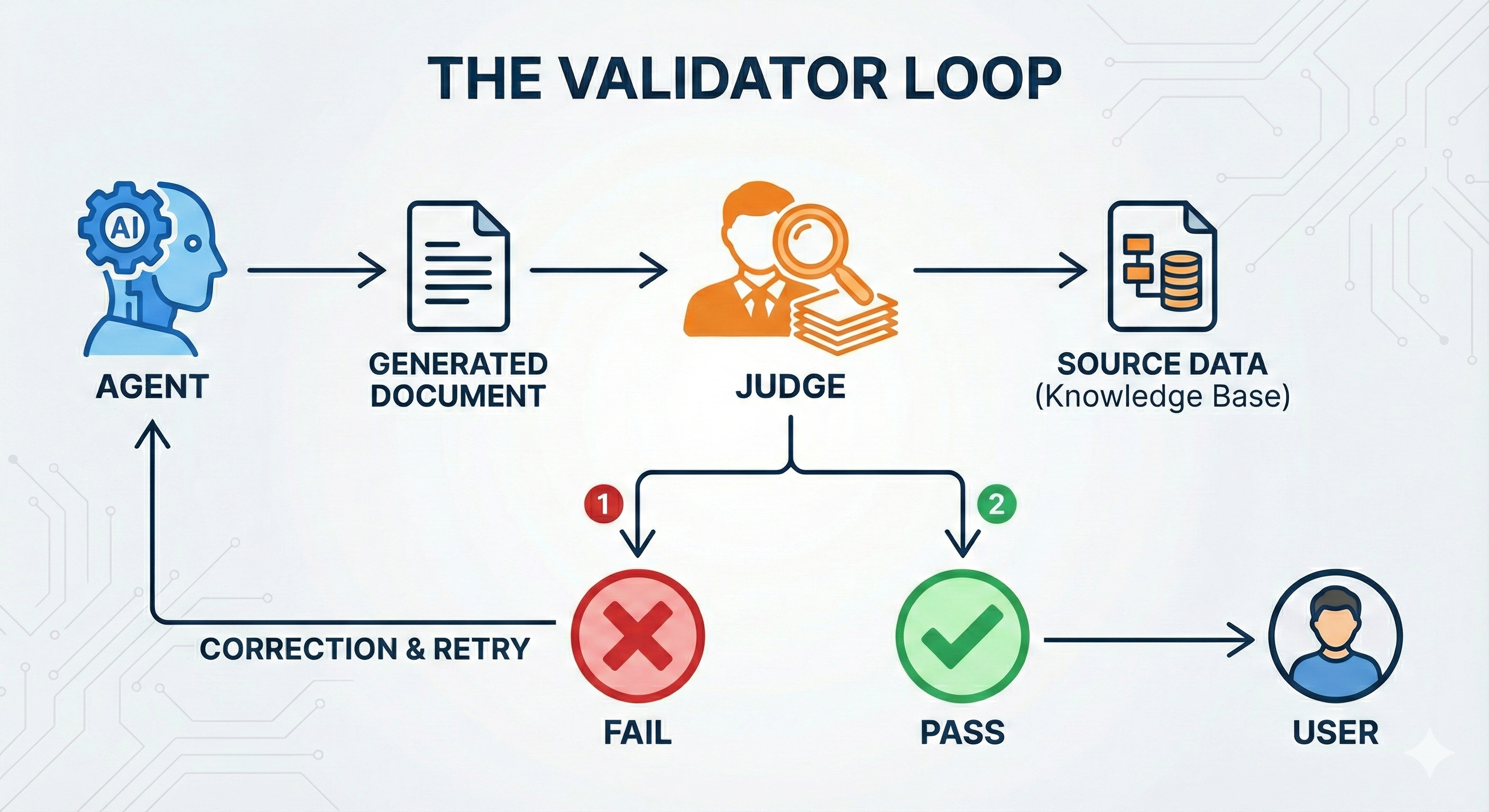

3. The Validation Loop: “LLM as a Judge” and ADK Loop Agents

In heavily regulated industries (Finance, Healthcare, Legal), “mostly right” is functionally equivalent to “wrong.” For these high-stakes, deterministic workflows, reliance on a single model pass is insufficient. Instead, an adversarial “LLM as a Judge” pattern is implemented, often utilising the Loop Agent construct within the Agent Development Kit.

This architecture effectively creates a “Four-Eyes Principle” for AI: one agent drafts the response, and a separate, isolated agent must approve it before it reaches the user or next stage.

Figure 4: LLM as a Judge and ADK Loop Agents

Figure 4: LLM as a Judge and ADK Loop Agents

The Architectural Separation: Creator vs. Critic

Crucially, the agent responsible for generating the answer (The Creator) and the agent responsible for validating it (The Critic) must have distinct system instructions and, ideally, different temperature settings.

- The Creator Agent: Optimised for fluency and synthesis.

- The Loop (Critic) Agent: Optimised for strict logic and scrutiny. It does not have access to the user’s conversation history in the same way; its scope is strictly to compare “Source Data” vs. “Generated Answer.”

The Critique Workflow

Before a response is finalised, it enters a validation loop governed by the following logic:

- Draft Generation: The primary agent generates a candidate response based on tool outputs.

- The Judicial Review: The Loop Agent analyses the candidate response against a strict rubric.

- Groundedness Check: “Does every claim in the generated answer map back to the provided tool output?”

- Negative Constraint Check: “Did the agent invent any advice not explicitly stated in the policy?”

- Hallucination Detection: “If the tool returned ‘No Data’, did the agent attempt to answer anyway?”

The Feedback Cycle:

- Pass: The response is released to the user.

- Fail: The Loop Agent rejects the response and returns structured feedback to the Creator Agent (e.g., “Rejected: You mentioned a discount code that does not exist in the CRM data. Retry and remove the hallucination.”).

- Retry: The Creator Agent generates a new response, correcting the specific error identified by the Critic.

Implementation in the ADK

The ADK facilitates this through Loop Agents. Rather than a linear chain, the workflow is configured to iterate.

Iteration Limits: To prevent infinite loops (where agents argue forever), a strict max_retries limit is defined. If the Creator Agent fails to satisfy the Judge after 3 attempts, the system defaults to a hard-coded error message (“I am unable to verify this information at this time”), effectively “failing safe.”

Atomic Validation: This validation isn’t just for the final answer. It can be applied to intermediate steps, e.g. validating an SQL query before execution or checking JSON formatting before an API call, ensuring hallucinations are caught upstream before they cause system errors.

The Result: This step acts as a firewall for hallucinations. It ensures that if the data isn’t in the source, the system is architecturally incapable of presenting it to the user.

4. Grounding and Context (Vertex AI)

Even with a flawless microservices architecture, an agent is only as reliable as the data it consumes. If you feed an agent irrelevant documents, it will hallucinate a connection to make them relevant. Therefore, RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) is not optional; it is the baseline.

However, standard RAG isn’t always enough. High precision architectures must rely on two specific capabilities to ensure precision:

- Domain-Specific Embeddings (Vertex AI Search) Out-of-the-box embedding models have a general understanding of the world. They know that “Java” relates to coffee and programming. But in a specialised industry, general understanding leads to retrieval errors, which lead to hallucinations.

The Problem: In the Oil & Gas sector, a “Christmas Tree” is a complex assembly of valves, not a holiday decoration. If a user asks about “Christmas Tree maintenance” and the model retrieves articles about pine needles, the agent will hallucinate.

The Solution: Fine-tuning Google’s foundation embedding models on the client’s specific corpus effectively retrains the model’s vocabulary. This mathematically shifts the vector space so it understands the specific jargon, acronyms, and relationships unique to that business.

The Result: The retrieval step becomes highly accurate, fetching the exact technical manual required. When the input context is perfect, the agent has no need to invent details.

Strict Enterprise Grounding

Leveraging the specific Grounding with Enterprise Data capability within Vertex AI acts as a final truth filter. This goes beyond simple context injection.

Forced Attribution: The model is configured to require citations. When the agent generates a response, it must be able to point to the specific chunk of text in the retrieved document that supports its claim.

The “I Don’t Know” Fallback: Setting high confidence thresholds on this grounding check dictates that if the model cannot find a direct citation in the provided enterprise data, it must return a fallback response (e.g., “I cannot find that information in the provided policy documents”) rather than leaning on its pre-trained internet knowledge.

The Result: This effectively switches off the model’s “creative” brain, forcing it to act solely as a synthesizer of the provided facts.

5. Continuous Vigilance: Evaluation and Monitoring

Ultimately, there is no magic bullet. Large Language Models are non-deterministic by nature, meaning that even a stable system can drift over time due to subtle changes in prompts, data underlying the RAG system, or model version updates. Therefore, deploying agents requires a shift from “deploy and forget” to active observability.

Automated Regression Testing (The Golden Dataset)

Reliance on manual testing is a bottleneck. Instead, a robust CI/CD pipeline for agents is built around Golden Evaluation Datasets. These are curated collections of “perfect” interactions, verified pairs of user inputs and the exact expected output (or tool call).

Vertex AI Evaluation: Using services like Vertex AI Evaluation, these datasets are run automatically against every new prompt iteration or model version. This acts as a unit test for intelligence: if a prompt tweak improves performance on Query A but causes the agent to hallucinate on Query B, the automated score drops, and the deployment is blocked.

Granular Tracing (Root Cause Analysis)

When an agent fails, it is rarely clear why immediately. Did it fail to find the document? Did it find the document but ignore it? Did it try to call the tool with the wrong ID?

Implementation of tracing is essential to visualise the entire Chain of Thought.

Retrieval Tracing: Verifying exactly which chunks of text were fed into the context window. If the correct answer wasn’t in the context, it is a Retrieval Failure, not a hallucination.

Reasoning Tracing: Inspecting the hidden “thought” steps of the agent. This reveals if the agent correctly identified the missing parameter but decided to “guess” it anyway (a clear sign of Reasoning Failure).

Metric-Driven Monitoring

Subjective “vibes” are replaced with quantifiable metrics. Using Model-Based Evaluation (where another model scores the outputs of the production agent), specific KPIs are tracked:

- Groundedness Score: A measure of attribution. Does every sentence in the response have a corresponding supporting fact in the retrieved context? A drop in this score is the leading indicator of hallucination.

- Faithfulness Score: A measure of adherence. Did the agent follow the negative constraints (e.g., “Do not mention competitors”) defined in the System Instructions?

- Tool Call Accuracy: A binary metric tracking how often the agent generates a schema-compliant JSON object versus how often it generates malformed parameters that cause API errors.

By treating these metrics like server latency or error rates, alerts can be triggered the moment an agent begins to drift, allowing for intervention before users lose trust.

Conclusion

Building agentic AI represents a fundamental shift. We aren’t building search engines that “know it all”; we are architecting digital workers that “know how to process.”

Hallucinations are inevitable in raw LLMs, but they are preventable in well-architected systems. By decomposing monolithic brains into orchestrated microservices, enforcing rigid contracts via schemas, and subjecting every output to a judicial loop, we replace probability with reliability.

The difference between a demo and a deployed product isn’t just the model’s capability, it’s the engineering rigour surrounding it. Ultimately, the goal isn’t just a smart agent; it’s a trustworthy one.